Did Seneca Have A Six Pack?

“Runners in a race ought to compete and strive to win as hard as they can, but by no means should they trip their competitors or give them a shove. So too in life; it is not wrong to seek after the things useful in life; but to do so while depriving someone else is not just.”

As someone who’s found huge personal meaning in both Stoicism and the joys of 5am long runs (I know, I apologise, I’m very dull at parties), it almost pains me to say this. But there’s nothing inherently Stoic about an early morning run, or any other kind of super healthy ‘morning routine’.

And yet talk of Stoicism is everywhere in fitness right now.

Why? Marcus Aurelius could not carry any boats. He lived with chronic pain, and also he was really busy trying to figure out if a person could be Emperor of Rome and a good person at the same time.

I’ve been thinking about what it all means. If you’ve got ten minutes, come with me and explore.

Stoicism 101

Let’s start at the very beginning. Who were the Stoics?

The most influential Stoic thinkers (guys like Epictetus, Marcus Aurelius and Seneca) wanted to help people live better lives by focusing on what they could control, rather than being at the mercy of emotions or external events.

At heart, they believed that if you can hold together a calm mind and a good character, you’ll have the keys to happiness, no matter what chaos the world throws your way.

At the risk of impossibly oversimplifying; here are some of the most important Stoic beliefs and practices.

Nothing truly belongs to you. Your life, your health, and everything you love might be taken from you at any moment. Practice thinking about all these things as borrowed, not owned: regularly sit and imagine life without each of them. Sounds grim? Far from it. This practice can be a powerful source of gratitude and joy.

We can’t control much. But we can control how we feel about it. What use is worry, or anger, in any situation we cannot change? Epictetus said, “I cannot escape death, but at least I can escape the fear of it.” When things are stressful, it can help to step back and see where we are able to have impact. Hold that space tightly: let go of everything else.

Then, do the right thing - be whole in your values and your actions - and ignore what other people think. We tend to care so much about the opinions of others, and rarely check in with ourselves. What is the right thing to do? What will we feel proud of ourselves for choosing?

Far from a miserable ‘getting through it’, this work can lead to more deeply understanding what we can impact, strengthening our resolve to make that impact, and also, fully experiencing what’s wonderful, right here and now.

“I have to die”, wrote Epictetus. “If it is now, well then I die now; if later, then now I will take my lunch, since the hour for lunch has arrived – and dying I will tend to later.”

Huberman and other problems

Right, so where does that all connect with six packs?

Because of who is talking about Stoicism right now, and which bits they’re cherry picking.

Ryan Holiday (the marketer who made American Apparel a thing, for what it’s worth), is largely credited as the writer who ‘brought back’ Stoicism, and in this new incarnation, it’s customised for grind culture. In the opening parable of Holiday’s bestseller ‘The Obstacle Is The Way’, a king places a boulder on a path. Some people go over it; some turn around. But the peasant who levers the rock out of the way finds a purse of gold.

Of course! If we buckle up and deal with hard things, we will be successful. Where Stoicism offers tools to part with the mentality of ‘success’. Holiday and his many friends sell a dream of riches.

Holiday selling his ‘2000 year old life hack’ on the Science of Success podcast.

Holiday is completely aware, by the way, that the version of Stoicism he’s selling is growing very far from its roots.

“We’ve only captured a very small fraction of the potential market”, he says. “Stoicism is a philosophy designed for the masses, and if it has to be simplified a bit to reach the masses, so be it.”

This Stoic Industrial Complex is just so lucrative. It comes neatly packaged on the bestseller lists with a side of Athletic Greens sponsorship. Alex Huberman designs us protocols to take with our powdered veggie drink; Jocko Willink shares a photo of his watch when he wakes up every morning at 4:30 - earlier than you, of course.

To participate we must buy it all, and post it on Strava. We must strive for an ultramarathon - and then one ultramarathon a day, and then an ultramarathon across the country, but also build massive biceps too - a feat that usually requires the purchase of extra hormones whether legally or otherwise. There is a graspingess to it all, a desire to cheat death rather than accept it.

And after all of this, it leaves us more alone than ever. Instead of coming together, we can focus intensely on the next rep, the next race: the complex pursuit of perfect health becomes a perfect distraction from thoughts that are so actually, monumentally hard to think about that even touching them is painful.

Stoicism can be a tool of community, a leaning in to share our resources without letting fear or selfishness rip us apart. But the open rates for that newsletter wouldn’t be great, and the supplement sponsors won’t pay.

What did the Stoics really have to say about exercise?

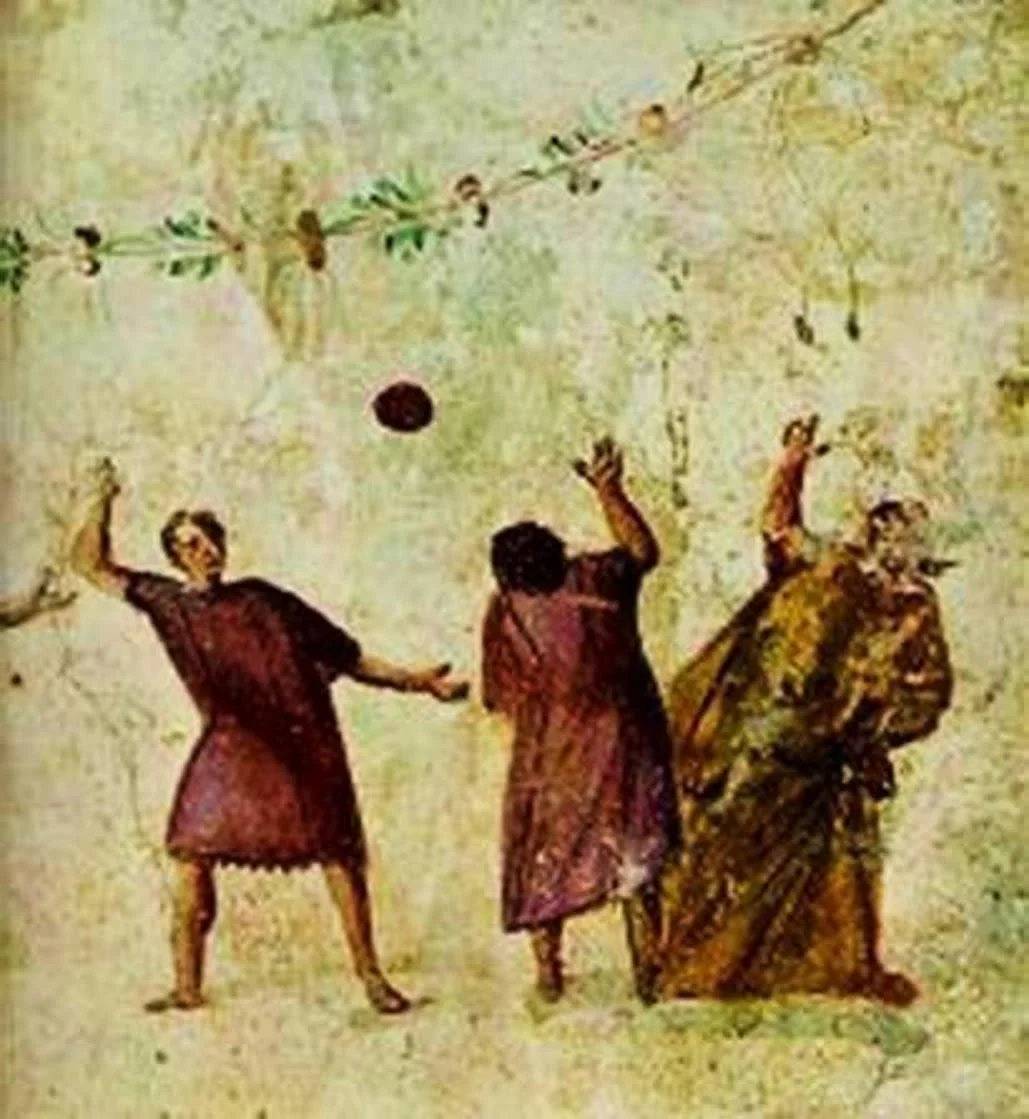

We still don’t know about the abs (sorry), but Seneca probably played a game or two of Harpastrum in his time.

The simple truth is the that Stoics had very little to say about physical exercise, beyond the fact that, look, you should do some.

That’s not to say they never talked about it. One of their more lovable traits is the way they understand how trapped we are in our bodies; how closely wound up our mental and physical states are. Seneca wrote that “..the first step to freedom is to take care of one’s health. If a man is diseased in body, his mind will also be diseased.” For those of us who live in female or less abled bodies, mind/body dualism has always been so glaringly daft an idea, but it’s everywhere and all around, all the time. So the Stoic acceptance that hey, look, if you don’t look after your meat sack, you probably won’t think particularly well, is quite nice to see.

But nowhere in the Encheirideon does Epictetus share his opinion on the perfect calf size; Marcus Aurelius was too busy trying to run an empire and deal with severe and chronic pain to get too worried about whether his delts were hot. It’s all just so… irrelevant.

To sum up how the Stoics felt, having a sexy six pack or being able to run really fast would be a ‘preferred indifferent’ - quite nice, but not worth actually striving for in the way that, say, working out how to be a good neighbour would be.

What would not be preferred would be making oneself rich off dodgy supplements. Sorry, podcast bros.

The hard part is not Bulgarian Split Squats

Right, let’s take a step back. Why do the new ‘Stoics’ talk so much about exercise? There are many things harder than getting at 5am. So why post so much about their rep ranges?

The easy answer is that what they’re doing is marketable. Nobody gets LMNT sponsorship without a thirsty Instagram account. But I think there’s also something deeper.

I think we can point this directly back at what the Stoics were trying to solve for in the first place: that being a human is living, impermanently, in scary psychic goo.

It’s perhaps because endurance exercise is a mid-size monster that makes it so attractive as a sales point. The Barkley Marathons might seem impossible to most, but surely less impossible than accepting that despite anything we do, our child may die; the powerful may start wars we cannot end and may not survive; things we love desperately will, if we are lucky enough to live, be lost. We buy the books precisely because, at a far stretch, we can imagine ourselves making it as tech entrepreneurs or finally taking on that huge ultra. These are possible impossibles.

No: the hard part is feeling everything, knowing we can’t stop it, and choosing to love and live and serve, despite it all.

But also, go for a run.

My eldest daughter, chasing ahead through the bush while I run. As a preferred indifferent, I prefer this quite a bit.

So, gosh, where does this leave us with that gym routine?

There are of course a few ways in which Stoicism can, I think inform exercise, and be practiced through exercise.

First - it can be a place to practice being OK with discomfort. If you’d like to get familiar with pain in short, manageable doses, your local Parkrun is free and they’d love to assist. And when things in life are just too, too hard, a long run and/or a long cry, depending on the headlines, do wonders to calm the spirit. For me, that’s often what controlling what you can control looks like on a day to day basis. My run or swim before the world wakes up isn’t really hard, even when it is: it’s more like a tool in my toolbox. The anxiety that follows me around in life like an annoying kid sister is quiet for a while, and if I’m lucky, that will last all day and inform what kind of person I show up as.

You can also practice gratitude out there: because the body you live in is the only one you have: take care of it, and thrive in it, and remember how lucky you are, if you have a body that can move, or a safe place to move it in.

Moving and getting stronger can heal us, calm us, and if we take friends along, connect us too. As a ‘preferred indifferent’, personally I prefer it quite a bit.

It’s just not, as they say, that deep. I have to die, as Epictetus said, and if I am lucky enough to live past lunchtime, I will also have to face things far harder than a 10K.

But I will tend to that later.

Right now, I’m going to lace up my shoes.